Alex Nowrasteh and Andrew Forrester just published a piece which they claim to show that, in the US, immigrants don’t litter more than natives. Here is how Nowrasteh, in his inimitable style, shared the piece on Twitter.

I started my career writing about how immigrants affect wages. Now I’m writing about how they affect the quantity of trash on city streets.

I haven’t changed, my opposition has.https://t.co/JXCCOJf2pM

— (((The Alex Nowrasteh))) (@AlexNowrasteh) December 11, 2019

Their post has been shared pretty widely and uncritically by pundits, academics and journalists and it’s already being used to argue that anyone who claims that immigrants litter more than natives is a racist. The problem is that, as I will argue in this post, not only does their analysis fail to show that immigrants don’t litter more than natives, but insofar as the data they used show anything, they show exactly the opposite.

Nowrasteh and Forrester claim to have been moved to write about this because, even though the issue seems a bit superficial, the argument that immigrants litter more is made increasingly often by restrictionists:

At the recent National Conservatism conference, University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax argued in favor of restricting non-white immigration to the United States because she said they litter more. My colleague David Bier was heckled at the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2018 and asked about immigrant littering. Fox News Tucker Carlson has been bringing up immigrant littering over the years, most recently with the help of City Journal associate editor Seth Barron.

If you ask me, this paragraph is extremely uncharitable, to the point of being dishonest. It makes his sound as if Carlson and Wax think the fact that non-white immigrants litter more alone justifies restricting non-white immigration, but obviously that’s not what they mean. They just use littering as one example of anti-social behaviors that, according to them, immigrants from certain parts of the world engage in more often than natives.

In fact, if you read what Wax said in her infamous talk (it was actually during the Q&A), she explicitly said as much:

I think we are going to sink back significantly into Third Worldism. We are going to go Venezuela, and you can just see it happening. I mean one of my pet peeves, one of my obsessions, is litter, and I… If you go up to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, or Yankee territory, right? Or versus other places that are “more diverse,” you are going to see an enormous difference. I’m sorry to report. You know, generalizations are not very pleasant, but little things like that, which aren’t little, they really affect our environment, attitudes towards public space.

I think Adam Garfinkle did a piece in The American Interest, where he talks about this—about noise levels, about the public space, about people’s deportment in public spaces, about respect for other people’s privacy, about things like heckling and, you know, sexual harassment. I mean all of this stuff sounds really silly, but when you add it up, these cultural habits, you know, make a difference to our environment.

And I think the celebration of diversity means that we lose some of these norms, these mores, that you know, make our life what it is. And I’m very concerned about it. Of course, it goes a lot deeper than that. Of course, it’s not just these superficial things, but I’m just mentioning that as emblematic of the way that I think we really are going, and nobody is willing to say anything about it, let alone try and stop it. I mean I guess I am, but…

I think it should be obvious to anyone with half a brain that, when people bring up littering in the context of the debate about immigration, they aren’t concerned about littering per se or just with littering. But in the case of Wax, since she even went out of her way to make that point explicitly, there is really no excuse to mischaracterize her view, not even stupidity.

Anyway, having explained why they felt the need to jump into this debate, Nowrasteh and Forrester describe how they allegedly showed that immigrants don’t litter more than natives:

Fortunately, there are data available to at least partially answer this question. The American Housing Survey (AHS) is a biennial longitudinal housing survey that asks about the amount of trash, litter, or junk in streets, lots, or properties within a half-block of the respondent’s housing unit. The answers are a “small amount of trash,” a “large amount,” and “no trash.” We constructed a scale from zero to one using a min-max normalization for all non-missing observations where a higher value indicates more trash in a neighborhood. We then take a weighted average of these scores using the weighting variable present in the AHS public use file for each metropolitan area.

The smallest geographical unit in the AHS was the Core-Based Statistical Area (CBSA) for 15 major urban areas in the United States that account for about 33 percent of the total U.S. population (around 58 percent of the foreign-born population and 30 percent of the native-born population). We linked the foreign-born shares of the CBSA populations from the 2017 American Community Survey (2013-2017, 5-year estimates) to the AHS survey responses on the amount of litter and trash. We then ran a regression where the independent variable is the percent of the CBSA’s population that is foreign-born and the dependent variable is the response to the litter question.

As they explain in the rest of the post, when they did that, they didn’t find statistically significant relationship between the proportion of immigrants in a CBSA and the amount of litter.

Now, as I will argue shortly, this analysis doesn’t make any sense, but just to be thorough I wanted to replicate it. Unfortunately, Nowrasteh and Forrester didn’t publish their code, so I asked the former on Twitter if I could have it, but he ignored me. This isn’t the first time he’s refused to share his code with me, since back when he published a paper on immigration and terrorism I had already asked him if I could have the code, but he had also ignored me. (EDIT: It turns out that, if Nowrasteh ignored me, it’s just because he didn’t see my requests. See the explanation at the end of the post, which I find convincing.) There is no good reason not to share your code. (This is why in my experience they never tell you why they don’t want to share their code, but either ignore you or give you some bullshit story about why they can’t.) The only reasons one might have not to share their code are bad. In particular, people are afraid that you’re going to find a mistake, which is actually one of the reasons why you should publish your code, even if there is a risk that you will end up looking bad. The published literature is probably full of errors that were never detected because only a handful of people ever had a look at the code.

In fact, one shouldn’t even have to ask, people should just publish their code along with their papers. This practice makes it easier for people to check your code for errors, replicate your analysis and perform their own analyses of the same data. Unfortunately, as I recently explained on Twitter, scientists face a collective problem, because while it’s good for science to provide your data and your code when you publish something, there is a strong incentive for individual scientists not to do it. (EDIT: I’m leaving the discussion of this problem because I think it’s important, but I want to be clear that I retract my criticism of Nowrasteh for ignoring me when I asked for his code, since I’m satisfied by his explanation that he didn’t see my requests.) If you do, you increase the risk that someone will find a mistake or use your work to make their own analysis, which of course is the whole point, but does not benefit you personally. Insofar as science is competitive in a variety of ways, if other scientists don’t do it, you have a strong incentive not to do it either. But this doesn’t excuse people who refuse to share their code, it merely explain why they do. This problem can only be solved by changing the incentives structure. This is why it should be a norm in science that, except when legal reasons prevent it, one should always provide one’s code and data when one publishes something. And people who don’t should be systematically shamed.

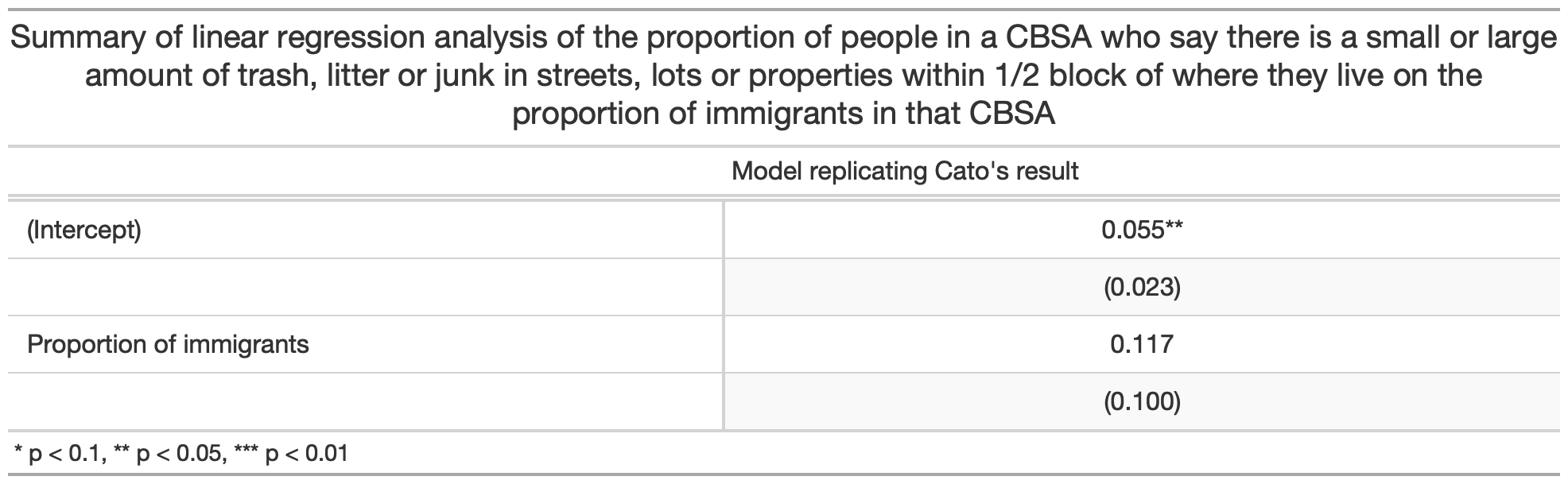

Anyway, in this case, it wasn’t very difficult to replicate the result, so it’s not a big deal. In fact, I didn’t do exactly the same thing as them, because I think using a min-max normalization to construct a scale coding the amount of trash in a respondent’s neighborhood and using that as the dependent variable makes the results of the analysis more difficult to interpret than they need to be. Instead, I kept the general approach of aggregating the data at the CBSA-level and checking whether there was a relationship between the share of immigrants in a CBSA and the amount of trash, but I used the proportion of people in a CBSA who say there is trash in the streets near their place of residence as the dependent variable. Since I practice what I preach, as per usual, I put my code on GitHub and the data are publicly accessible.

Although I did something slightly different from what Nowrasteh and Forrester did, the result was essentially the same. As you can see, although the coefficient of the independent variable is positive, the standard error is huge and it’s not statistically significant.

As you can see, although the coefficient of the independent variable is positive, the standard error is huge and it’s not statistically significant.

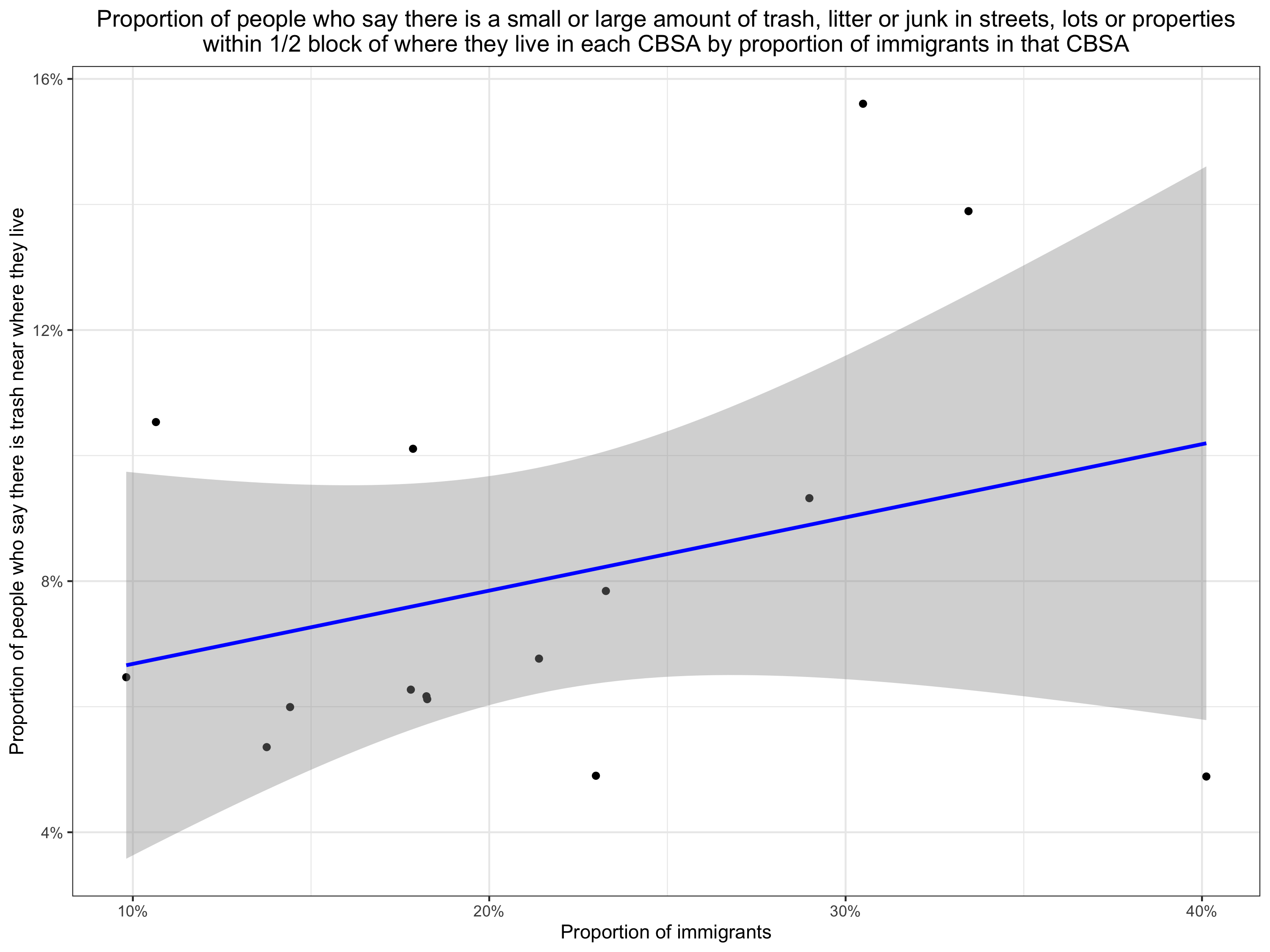

If I plot the observations and the regression line, the results looks a lot like the plot in Nowrasteh and Forrester’s post. The slope is positive, but it’s very imprecisely estimated, as you can see from the error band.

The slope is positive, but it’s very imprecisely estimated, as you can see from the error band.

So far, so good. But does it mean that Nowrasteh and Forrester are right and that immigrants don’t litter more than natives? Well, no, it does not. Not at all. The way they analyzed the data makes absolutely no sense and, when you do it correctly, you find exactly the opposite result. In fact, insofar as the data show anything, they completely vindicate Wax, but amazingly Nowrasteh and Forrester reached exactly the opposite conclusion. The problems with their analysis are so obvious that, when I read their post, I just couldn’t believe it. The dataset they used contains more than 50,000 observations, but by aggregating at the CBSA level, they reduced that to only 15 observations. The only reason to use this approach is that, by doing that, we can precisely determine the demographics of the area where respondents live instead of using their own demographics for the composition of their neighborhood. But the CBSAs in the dataset are huge and contain a lot of people, whereas respondents were asked about the presence of trash in the streets within 1/2 block of where they live, so this is not helpful.

It’s true that, if immigrants litter more, you would expect that, other things being equal, a greater share of immigrants in a CBSA would increase the proportion of people in that area who say there is trash near where they live, because immigrants would litter in their own neighborhoods and because even natives are more likely to live around immigrants in areas where immigrants are a larger share of the population. (So you would also expect the association between the immigration status of respondents in a CBSA and the proportion of those who report the presence of trash in their neighborhood to be moderated by the amount of residential segregation in that area.) But other things are almost certainly not equal, since many other factors could affect the amount of trash in the streets and some of them are probably correlated with the share of immigrants in the population, so we shouldn’t expect a bivariate relationship between the share of immigrants in the population and the proportion of respondents who report the presence of trash in the streets even if immigrants litter more.

Even if the share of immigrants in a CBSA were the only factor affecting the amount of trash in that area and other factors were not correlated with it, a regression with only 15 observations has very little power to detect even a pretty large effect. In fact, although it’s very imprecisely estimated and not significant, the slope of the regression is still positive, so it could be that there is a positive bivariate association between the share of immigrants and the share of people who report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live. But I wouldn’t put much stock in that, because there are no doubt many other factors that affect the amount of trash in a CBSA, some of which are probably correlated with the share of immigrants. Indeed, CBSAs differ in their racial, socio-economic, etc. composition and many other more idiosyncratic things which could affect the amount of trash in the streets. For instance, perhaps Seattle has very good waste disposal services, whereas in Newark waste disposal is controlled by the mob and it’s very bad. In that case, since the share of immigrants in the population is also much larger in Newark than in Seattle, this could hide the effect that immigrants have on the amount of trash in the streets.

Thus, in this case, a bivariate analysis at the CBSA level is completely useless. Moreover, we can’t include other covariates in the model, because power, which as we have seen is already very low, would go down even more if we did that. It makes a lot more sense to analyze the data at the individual level. Since immigrants tend to live around each other and the American Housing Survey asked respondents to describe how much trash their was in the streets within 1/2 block of where they live, which is a very small area, if immigrants litter more, we have a much better chance of detecting it than if we aggregate at the CBSA level, especially since the CBSAs in the dataset are huge and each of them contains millions of people, because presumably the immigration status of respondents is a decent if noisy proxy of the share of immigrants in their neighborhood. (Again, this means that, if immigrants litter more, we’d expect the association between the immigration status of respondents and how they answer the question about the presence of trash in their neighborhood to be moderated by the amount of residential segregation in the area where they live.) Of course, if we analyze the data at the individual level, omitted variable bias is also a problem because, even if a respondent’s place of birth were not a noisy proxy for the share of immigrants in his neighborhood, any relationship between the share of immigrants in a neighborhood and the amount of trash in that neighborhood could be confounded by other factors, but since the sample size is huge we actually have the power to control for some of them.

So why did Nowrasteh and Forrester aggregate the data at the CBSA level? Honestly, this makes so little sense that I find it hard not to believe that what happened is that they started by looking at the data at the individual level, didn’t like what they found and therefore came up with this contrived way of analyzing them. At the very least, they should have looked at the data both at the CBSA level and at the individual level, instead of just analyzing them at the CBSA level and concluding they undermine Wax’s claim, when as we shall see the analysis at the individual level completely vindicates her. The fact that it would have been much better to be able to determine the demographics of the neighborhoods of respondents directly, instead of relying on their individual characteristics as proxies for the characteristics of their neighborhoods, is not a reason to throw away virtually all the information contained in the dataset, but that is exactly what they did. I don’t think there is any excuse for that and I find it extraordinary that none of the social scientists who shared their post noted this problem.

Another problem is that Nowrasteh and Forrester didn’t disaggregate the group of immigrants by race and/or origin, but people like Wax explicitly focus on non-white immigrants and, in the case of the debate about littering, it’s hispanic immigrants that are most often singled out. (However, since again the approach they used is severely misguided, it wouldn’t have helped.) In fact, Wax’s main point is that we can’t look at immigrants in general, we must distinguish between them depending on where they come from. Looking at immigrants in general, instead of disaggregating by country/region of origin, is a trick pro-immigration advocates use all the time, but it’s totally dishonest. For most outcomes, there is a lot of heterogeneity between immigrants depending on where they come from, so that some immigrant groups do well and others do poorly. Thus, if you look at how immigrants do on average, you often find that they do okay, but usually that’s just because the groups that do well make up for the groups that do poorly.

In general, when people complain about “immigration”, even if they don’t use any qualifier, they are only complaining about some groups of immigrants but not all of them, so the average effect of immigrants is irrelevant to their claims. For instance, when people in France complain about immigration, everybody knows they’re talking about African and North-African immigrants. I have almost never heard anyone complain about Asian immigrants, because they tend to do very well and don’t cause many problems. Thus, if we are going to use the American Housing Survey to assess whether people like Carlson and Wax are right, we must disaggregate by region of origin and/or race, which Nowrasteh and Forrester didn’t do. Again, even if they had, it wouldn’t have shown anything one way or the other, because it would have done nothing to alleviate the problems with their methodology that I described above.

Finally, restrictionists about immigration don’t just talk about immigrants, but also about their descendants, because their central point is that neither immigrants nor even their descendants magically adopt the culture of their country of destination just in virtue of living there. You may think that it’s wrong, although it clearly isn’t, but in any case that’s the claim they make, so you can’t possibly refute it by just looking at immigrants. Indeed, just looking at immigrants and ignoring the effects of their descendants is another trick that pro-immigration advocates often use, but the effects of immigration are not limited to the effects of immigrants themselves. It also includes, among other things, the effects their descendants have. In fact, if you go back to Wax’s answer where she talked about littering, you will see that she doesn’t even talk about immigrants. She claims that littering is worse in areas that are more “diverse”, so she isn’t making a point about immigration per se but about race/ethnicity, although those issues are obviously related. Thus, if we want to use the American Housing Survey to assess whether she is right, we have to examine whether race/ethnicity, not just place of birth, is related to littering.

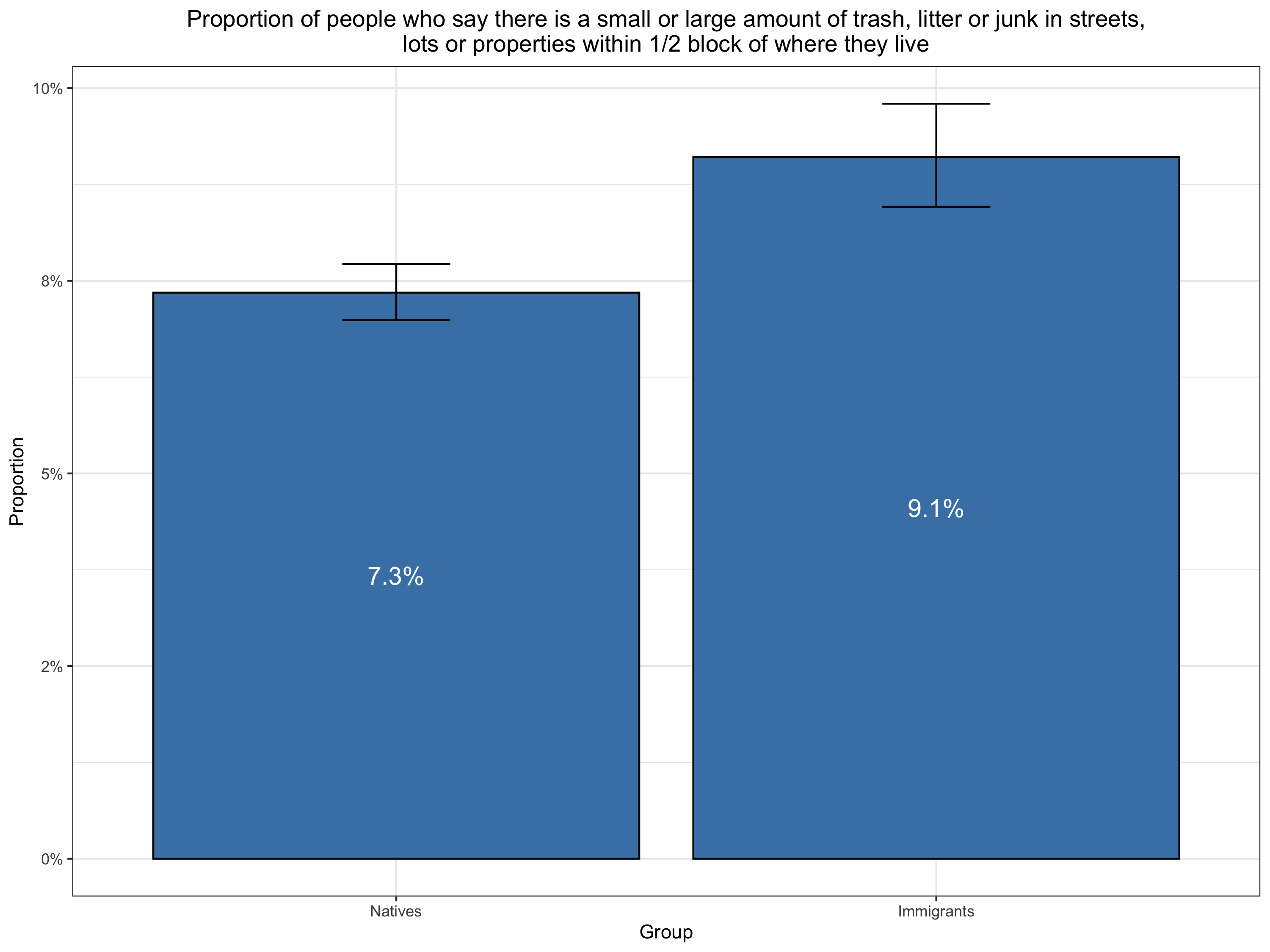

Even though I have just explained that one should disaggregate between immigrants depending on region of origin, let’s first see whether, when the data are analyzed at the individual level, we find a difference between natives and immigrants. As you can see on this chart, where I represented the confidence intervals, there is a statistically different between immigrants and natives, so the answer is yes.

As you can see on this chart, where I represented the confidence intervals, there is a statistically different between immigrants and natives, so the answer is yes.

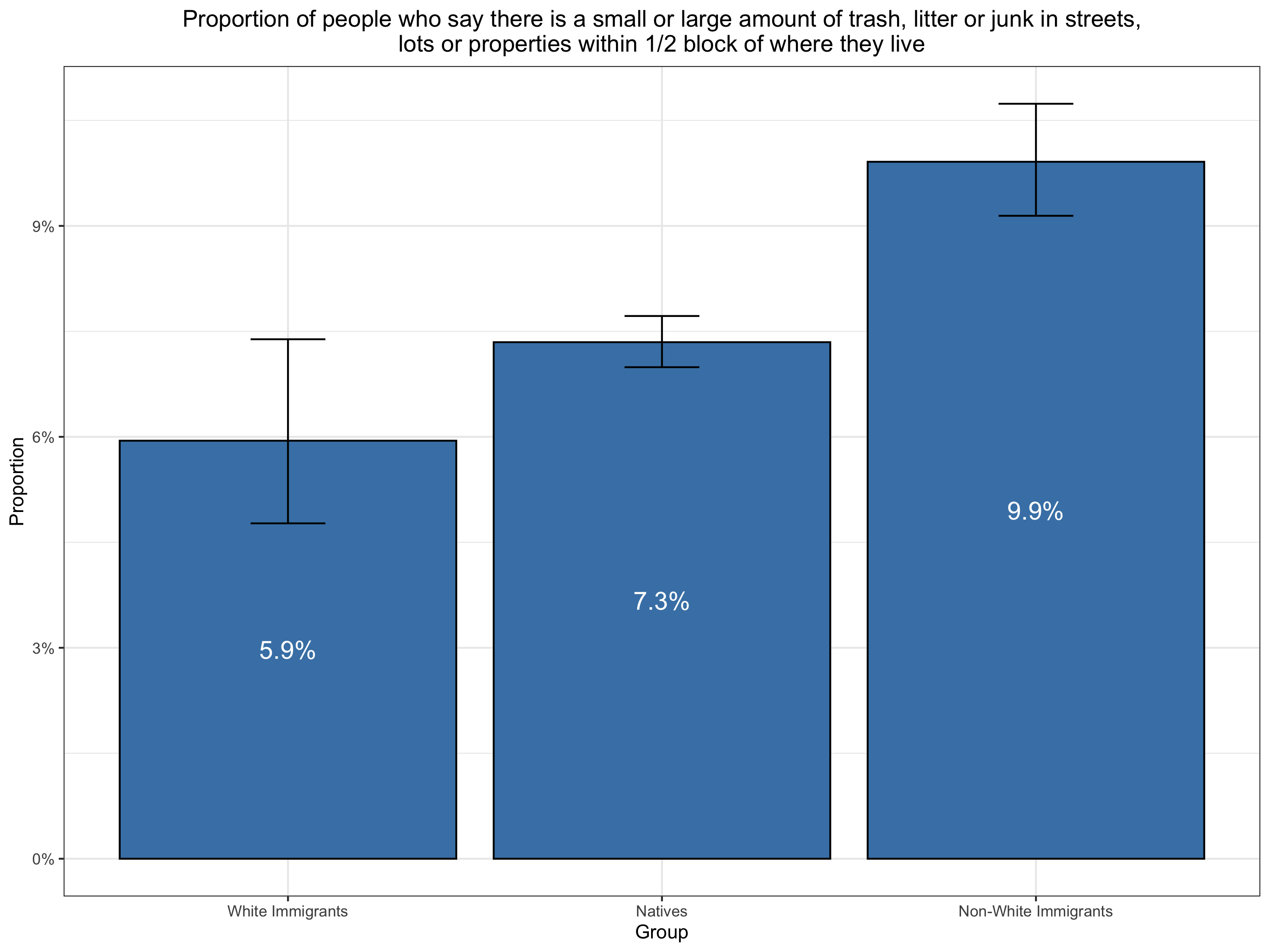

Next, since Wax singles out non-white immigrants, let’s see what happens when we disaggregate the group of immigrants into white and non-white immigrants. Well, look at that, it turns out that not disaggregating hid a significant difference between white and non-white immigrants. I wonder who could have predicted that? Well, I guess we know at least one person who had predicted it, Amy “the horrible racist” Wax.

Well, look at that, it turns out that not disaggregating hid a significant difference between white and non-white immigrants. I wonder who could have predicted that? Well, I guess we know at least one person who had predicted it, Amy “the horrible racist” Wax.

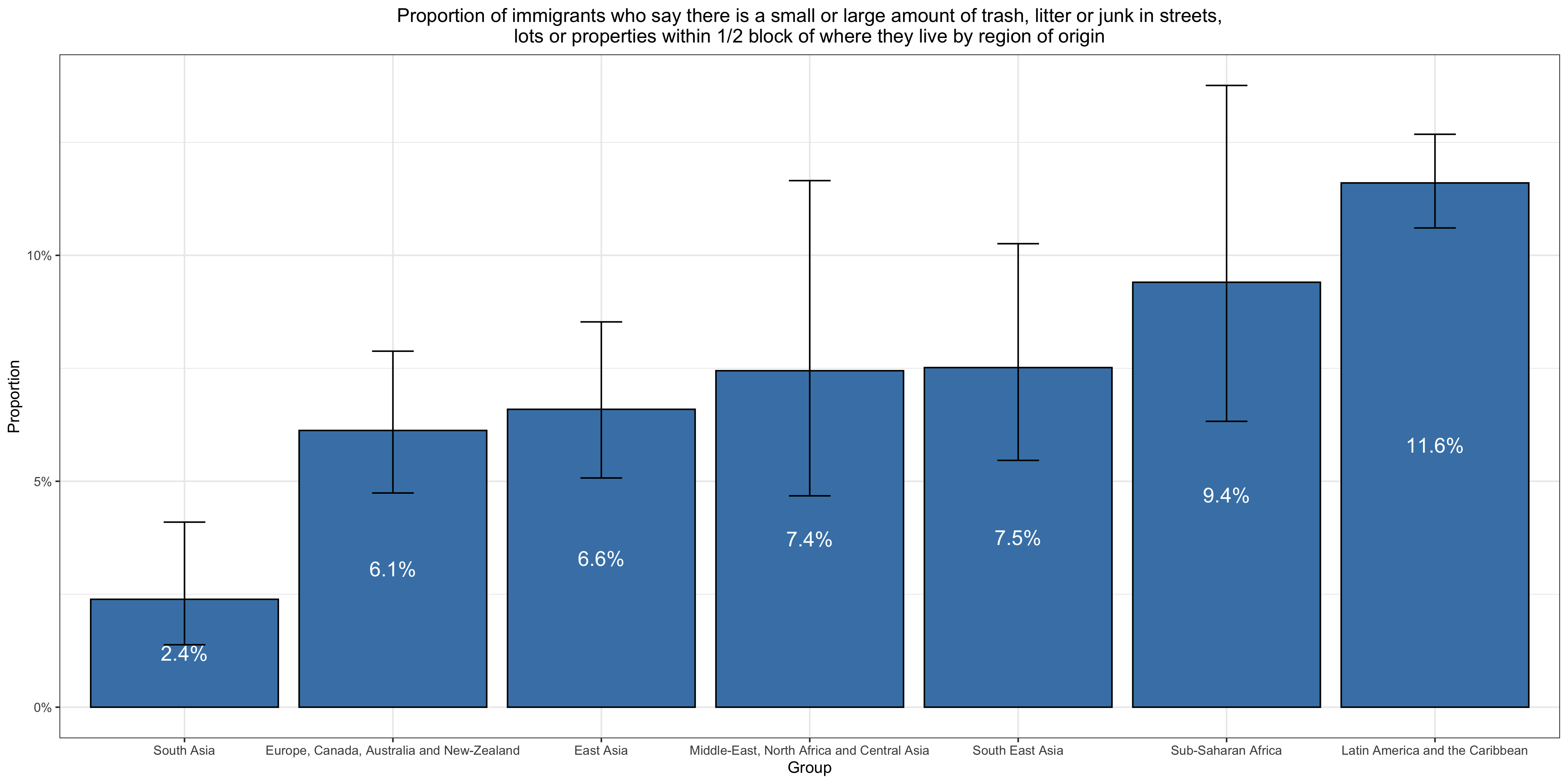

But the white/non-white dichotomy is still very crude and no doubt hides a lot of heterogeneity, so let’s focus on immigrants and disaggregate further based on where they come from. As you can see, for most groups of immigrants, there is no way to know for sure whether they are less or more likely than natives to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live. But this is not true for immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, who are significantly more likely than natives to do so. As it happens, when people say that immigrants litter more than natives, hispanic immigrants are precisely the group they usually single out. Thus, far from undermining this claim, the data seem to support it. It should also be noted that South Asians are significantly less likely to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, but I’ve never heard anyone complain that Indian immigrants litter…

As you can see, for most groups of immigrants, there is no way to know for sure whether they are less or more likely than natives to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live. But this is not true for immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, who are significantly more likely than natives to do so. As it happens, when people say that immigrants litter more than natives, hispanic immigrants are precisely the group they usually single out. Thus, far from undermining this claim, the data seem to support it. It should also be noted that South Asians are significantly less likely to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, but I’ve never heard anyone complain that Indian immigrants litter…

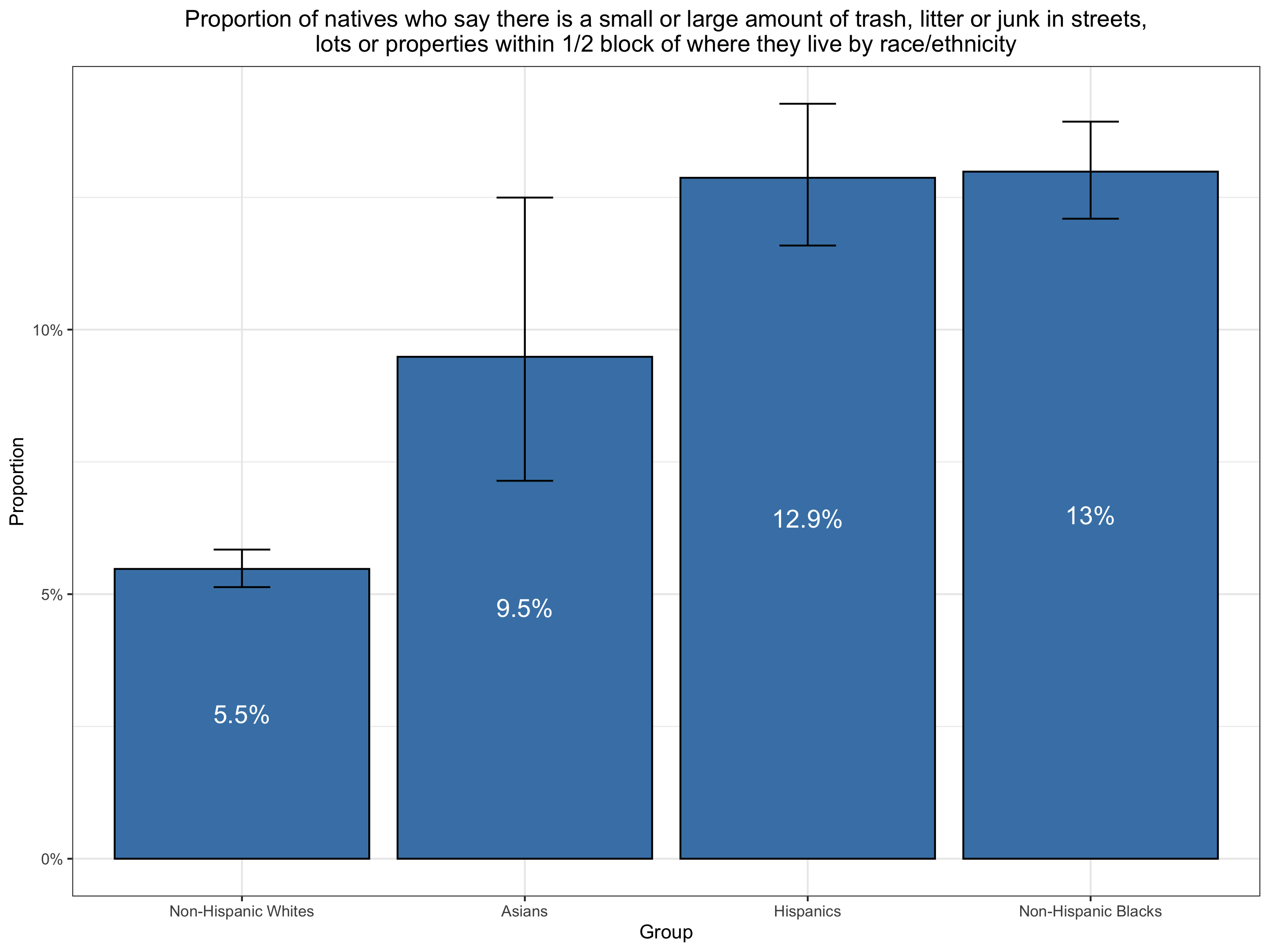

Finally, as I have explained above, people like Wax are not just concerned about immigrants themselves, but also about their descendants. Even if immigrants litter more than natives, it may not be a big deal as long as their descendants, having been socialized in the US, had adopted the local norms and behaved similarly to natives with respect to littering. In order to check whether the data supports this hypothesis, let’s look only at natives and disaggregate by race/ethnicity. Unfortunately, it looks as though reality refuses to cooperate, as it often does.

Unfortunately, it looks as though reality refuses to cooperate, as it often does.

Not only are native-born hispanics no less likely than immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, but they may even be more likely, though we can’t say that for sure because the proportions are not estimated precisely enough. Among native-born individuals, non-hispanic blacks are also significantly more likely to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, though most of them are not the descendants of immigrants. Even native-born Asians, who do very well by most other metrics, are more likely than natives to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood. It’s not uncommon for second-generation immigrants to do worse than their parents on some metrics, so this result is not entirely surprising. For instance, although hispanic immigrants seem to commit less crime than even non-hispanic white natives, there is evidence the opposite is true of their descendants. (In fact, I think the evidence is overwhelming, but I would need another post to make the case, which I probably will eventually because this undermines a common argument of pro-immigration advocates in the US.) This phenomenon is so common that social scientists even have a name for it, the immigrant paradox, so again the result I found above is not particularly surprising. In any case, this result clearly supports Wax’s claim, yet Nowrasteh and Forrester, who analyzed the same dataset, claim the data undermine it.

However, although some groups of immigrants, especially immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, are more likely to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, this may not be because they are culturally disposed toward littering. With the kind of data I’m analyzing in this post, we can never know for sure, but we can use multivariate analysis to get a better sense of what is going on. Thus, in order to understand better what explains the patterns we have observed, I have used logistic regression analysis to model the probability that a person reports the presence of trash in the streets near where they live. The coefficients of the independent variables in a logistic regression are a bit difficult to interpret, but in a nutshell, they tell you how each variable affects the odds that someone will report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, which can be translated into a ratio of probabilities by assuming a base rate.

The coefficients of the independent variables in a logistic regression are a bit difficult to interpret, but in a nutshell, they tell you how each variable affects the odds that someone will report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, which can be translated into a ratio of probabilities by assuming a base rate.

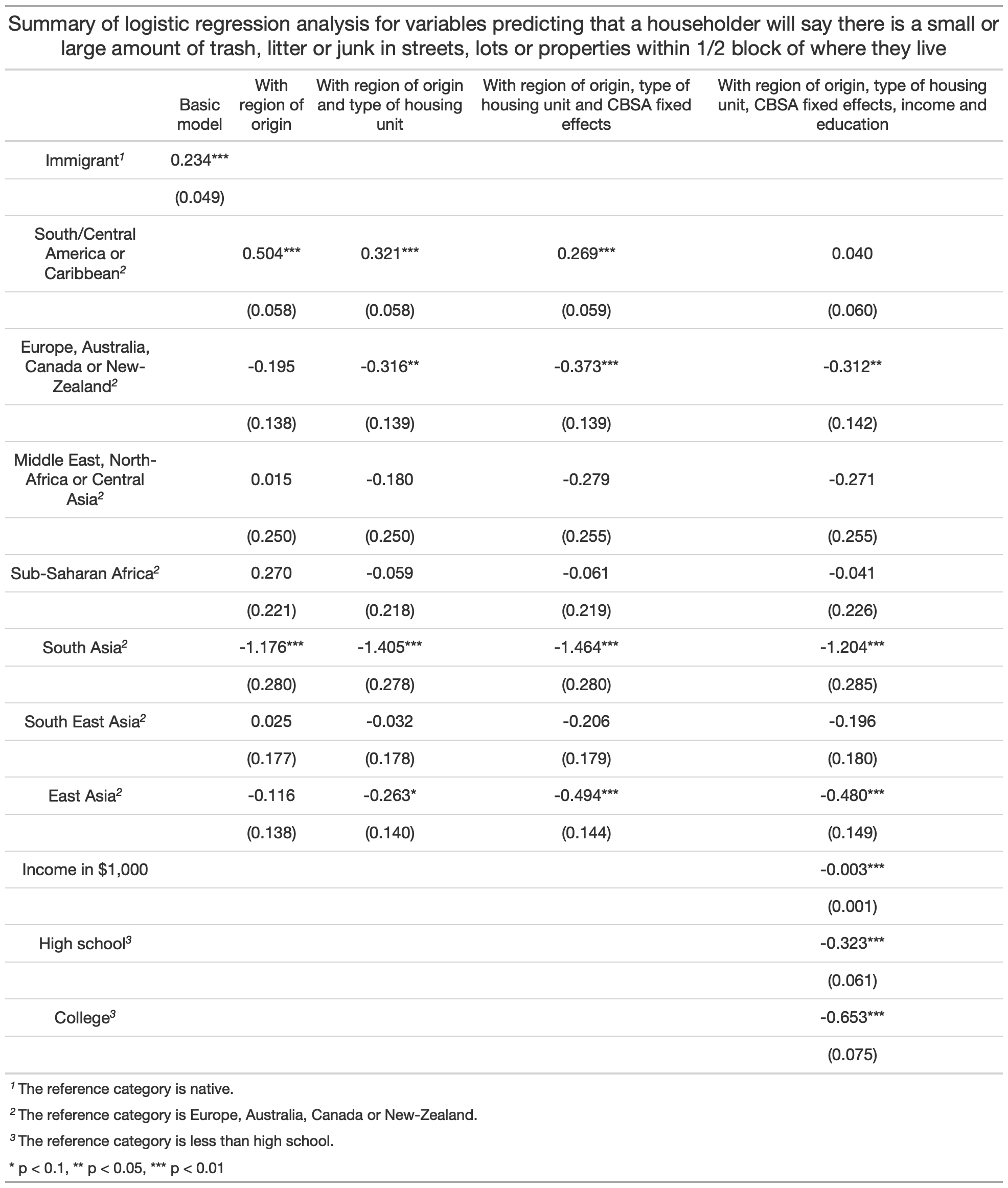

For instance, in the basic model, which only includes a variable indicating whether the respondent is an immigrant, the coefficient is 0.234 and it’s statistically significant. This is the logarithm of the ratio of the odds of reporting the presence of trash near where they live for immigrants to the odds of doing so for natives. By taking the exponential of this number, we get the odds ratio in question, which is approximately 1.26. If we take as base rate the probability of reporting the presence of trash near where they live for natives, which as we have seen is about 7.3%, this translates into a ratio of probabilities of approximately 1.24. Thus, according to this model, immigrants are approximately 24% more likely than natives to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live or about 1.7 percentage points. So the model predicts that approximately 9.1% of immigrants should report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live, which unsurprisingly is exactly what we found above by calculating the proportion directly.

Since as I have explained, we are not so much interested in the average effect for immigrants as much as the effect for immigrants from different regions of the world, in the second model, I have included a bunch of dummy variables whose coefficients tell us how being an immigrant from each of those regions affects the odds of reporting the presence of trash in the streets near where you live. Again, since the model doesn’t include any other covariates, this doesn’t tell us anything that we didn’t already know. For instance, the coefficient for immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean is 0.504, which by the same reasoning as above means that immigrants from this region are approximately 58% more likely than natives to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood or about 4.2 percentage points, which is exactly what we had found above by the direct method.

But it’s possible that, if some immigrants are more likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood, it’s not because immigrants from the same region of the world as them litter more, but because they just happen to be concentrated in areas where, for some other reasons, there is more trash in the streets, so everyone is more likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood, whether they are immigrants or natives. For instance, perhaps immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean are concentrated in areas where the authorities do a poor job at waste disposal, in which case they would report more trash in the streets of their neighborhood than natives even if they don’t litter more than them, just because they are not geographically distributed in the same way. In order to rule out this hypothesis, I have included CBSA fixed effects in the third model. As you can see in the table above, this does reduce somewhat the coefficient of the dummy variable for immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, but it remains statistically significant and large.

In fact, the coefficient is reduced for every region of origin, but it doesn’t affect statistical significance except for immigrants from East Asia and Europe, Australia, Canada and New-Zealand, who now appear to be less likely than natives to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood. However, one must be careful in the interpretation of this result, because it could be misleading. As I explained above, CBSA fixed effects are going to absorb any idiosyncratic effects that living in a particular CBSA has on the probability that you report the presence of trash in your neighborhood. The problem is that, while those idiosyncratic effects might have nothing to do with immigration, they might also be at least in part the result of immigration. In particular, it may be that, if immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean live in areas where everyone, immigrants and natives, say there is more trash in the streets near their home, it’s partly because those are areas where there are lots of immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean.

Indeed, suppose that the proportion of immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean in a CBSA is causally related to the amount of littering in that area because they litter more than other people, then by adding CBSA fixed effects we are not only removing the effect of idiosyncratic factors like how well the authorities handle waste disposal in each CBSA, but also part of the effect of the presence of immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean. The problem is that, although residential segregation means that immigrants from the same region tend to live around each other, the proportion of people from South/Central America and the Caribbean in every neighborhood still increases with their share of the population in a CBSA. Thus, if immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean litter more, you would expect everyone, not just immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, to be more likely to report the presence of trash within 1/2 block of where they live in CBSAs where immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean are a greater share of the population.

In a nutshell, the problem is that CBSA fixed effects remove any between-CBSA variation from the analysis, including variation that is due to between-CBSA differences in the share of immigrants in the population. If the dataset contained information about the location of respondents at a smaller geographic scale than the CBSA, such as the Census tract, this wouldn’t be a problem, because we could use the share of immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean in each Census tract as the independent variable for the analysis instead of relying on the country of origin of respondents as a proxy for the presence of immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean in their neighborhood and we could use regional fixed effects without having to worry about that problem. But the public use file doesn’t contain this information, so we have to rely on the individual characteristics of respondents.

If we’re trying to estimate the effect immigrants from East Asia have on the amount of trash in the streets and they happen to be concentrated in areas where there are lots of immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, it might be entirely appropriate to include CBSA fixed effects, since it will reduce the coefficient of the dummy variable for this group of immigrants. But as I just explained, this will also reduce the coefficient of the dummy variable for immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean and, in this case, it will be misleading since, on the hypothesis I made, they litter more. Moreover, if immigrants from East Asia also litter more, including CBSA fixed effects will not only control for the fact that immigrants from that region of the world tend to live around immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean, but it will also bias downward the effect we are trying to estimate. Of course, this is also a problem for the analysis I perform below, where I use race/ethnicity dummies instead of dummies for immigrants from different regions of the world and include CBSA fixed effects in some models. Unfortunately, there isn’t much we can do about it, this is just a reminder that causal inference is tricky and that it’s never straightforward to infer causal relations from the results of a regression.

Finally, in the last model, I added covariates for income and education. The idea is that, since people tend to live around people with similar socio-economic characteristics, the income and education of respondents should be a proxy for the socio-economic composition of their neighborhood. It would have been better if we could have used the socio-economic composition of the neighborhoods where the respondents live, but the data don’t allow it since the smallest geographic areas in the dataset are CBSAs, which are pretty huge. As you can see, once you control for income and education, the coefficient of the dummy variable for immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean is still positive but it’s no longer statistically significant. Income and education are associated with the probability of reporting the presence of trash in the streets near where respondents live exactly as you would have assumed. Namely, the more people make and the less likely they are to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood and, the more educated they are, the less likely they are to do so. This result suggests that, once you control for income and education, as well as geographic distribution, immigrants from this region are no more likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood than natives. However, even more than in the case of CBSA fixed effects, adding covariates for income and education in the model might not be a good idea, so we have to think carefully about what question we are trying to answer and what is the best model for that purpose.

The result I just described doesn’t even mean that, if immigrants from South/Central America and the Caribbean were as rich and educated as the average native, they would not litter more (because we can’t infer a counterfactual from this purely observational result), it just means that, when you compare immigrants from that region, most of whom are poor and uneducated, to similarly poor and uneducated natives, it’s not clear they litter more. But even if it did mean that, the people who complain that hispanic immigrants litter more than natives presumably wouldn’t give a damn, because the fact is that most hispanic immigrants are poor and uneducated relative to natives. People like Wax don’t care about a hypothetical situation in which hispanic immigrants have magically become rich and educated, they care about the actual situation in which most of them are poor and uneducated. Similarly, when I say that, in France and in the rest of Europe, immigrants from Africa and North-Africa commit more crimes than natives, people often reply that it’s just because they’re poorer and less educated. But even if that were true, which it isn’t, this would hardly be comforting for people who were stabbed, raped, etc. by African/North-African immigrants.

You could say that, to the extent they ascribe the greater propensity to litter of hispanic immigrants to their culture, this result is evidence they are wrong, but even that is not true, because I’m sure Wax would have no problem acknowledging that, even among natives, different socio-economic groups have different cultures and this affects how often they engage in various anti-social behaviors. In fact, that different groups of natives don’t have the same culture is a commonplace, which rightly or wrongly people bring up to explain a lot of phenomena. In particular, the problems of poor people are often blamed on the “culture of poverty”, which according to this theory makes people engage in anti-social and self-defeating behaviors. Similarly, in the debate about the problems faced by African-Americans, people often allege that many of them are caused by the dysfunctional culture that prevails in many predominantly African-American neighborhoods. Obviously, Wax isn’t going to think that it’s okay to import a dysfunctional underclass from abroad just because it’s no more dysfunctional than the native-born underclass, since it will damage American society all the same.

However, that is not to say that controlling for income and education is entirely a bad idea, even if we’re interested in assessing whether Wax is right. Indeed, it’s possible that, if poor and uneducated people are more likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood, it’s not only because they are culturally disposed to litter more, but in part because the authorities care less about them and/or low-information people don’t know how to use the system to force them to care, so they don’t get waste disposal service as good as rich and high-information people. Since poor and uneducated people tend to live around each other, if this were the case, we’d expect respondents to the American Housing Survey to be more likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood even if poor and uneducated people did not litter more, which they almost certainly do. Again, we have no way of disentangling those different mechanisms, so there is no good solution. If we include covariates for income and education, we are probably biasing downward the estimate of the effect we are interested in, but if we don’t then we are probably biasing it upward.

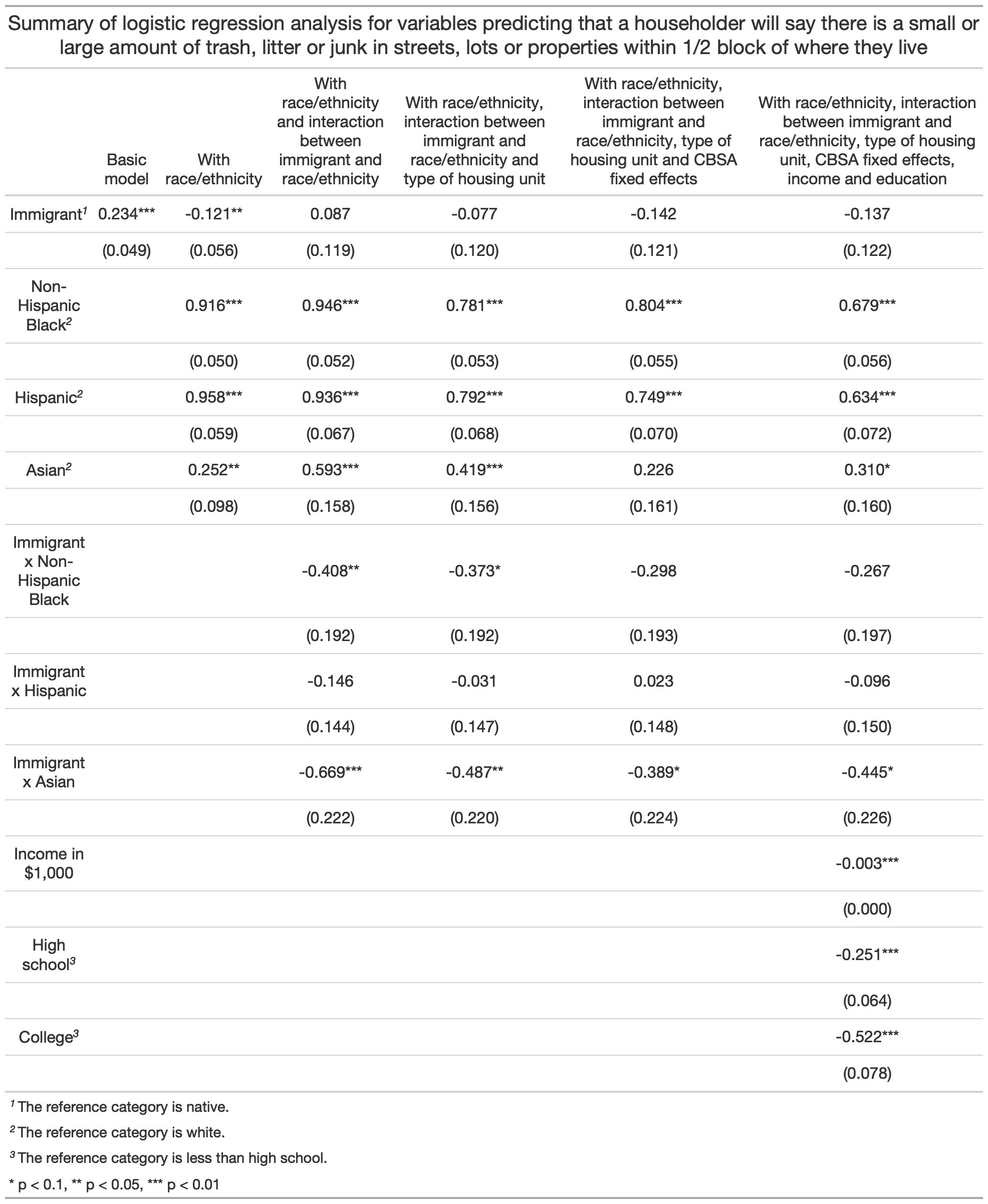

One thing we can do to shed more light on the issue is use a different approach and, instead of having a distinct dummy variable for each type of immigrants, we just keep the immigrant variable and control for race/ethnicity, as well as CBSA, income and education. Again, the assumption is that people tend to live around people of the same race/ethnicity, so the race of respondents is a proxy for the racial/ethnic composition of their neighborhood and the rate at which people in different racial/ethnic groups report the presence of trash in their neighborhood is a proxy for the tendency of people in each group to litter. This approach also has the advantage that it can reveal differences between racial/ethnic groups among natives. As we have seen, Wax’s concern isn’t limited to immigrants themselves, but also to their descendants, so this is desirable in the context of a discussion of her claim about littering. We could also have used the dummy variables for the different groups of immigrants instead of the immigrant variable, but although racial/ethnic categories don’t line up exactly with regions of origin (which can make the interpretation of the kind of model I’m contemplating here tricky), they still line up enough that multicollinearity is a concern. Instead I added interaction terms between the immigrant variable and the race/ethnicity dummies in some of the models.

This approach also has the advantage that it can reveal differences between racial/ethnic groups among natives. As we have seen, Wax’s concern isn’t limited to immigrants themselves, but also to their descendants, so this is desirable in the context of a discussion of her claim about littering. We could also have used the dummy variables for the different groups of immigrants instead of the immigrant variable, but although racial/ethnic categories don’t line up exactly with regions of origin (which can make the interpretation of the kind of model I’m contemplating here tricky), they still line up enough that multicollinearity is a concern. Instead I added interaction terms between the immigrant variable and the race/ethnicity dummies in some of the models.

As you can see, in the second model (where I just controlled for race/ethnicity), the coefficient of the immigrant variable becomes negative. This suggests that being foreign-born per se doesn’t make you more likely to report the presence of trash in your neighborhood, but not being white does. Indeed, according to this model, blacks, hispanics and, to a lesser extent, Asians are significantly more likely to report the presence of trash in the streets near where they live. Needless to say, this is a complete vindication of Wax, who as we have seen claimed that more “diverse” areas had more littering. However, if immigrants belonging to certain racial/ethnic group are less likely to litter than natives of the same group, this model will be misleading. Thus, in the third model, I added interaction terms between the immigrant variable and the race/ethnicity dummies. As you can see, the coefficient of the immigrant variable is now statistically indistinguishable from zero, which suggests that white immigrants are just as likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhood as white natives. The coefficients of the race/ethnicity dummies remain very large and, in the case of Asians, it even increases substantially. On the other hand, the coefficients of the interaction terms are all negative, though it’s not significant in the case of hispanic immigrants. The results are essentially unchanged in the fourth and fifth models, which add CBSA fixed effects and controls for income and education, respectively.

What this analysis suggests is that, although immigrants are more likely to report trash in their neighborhood than natives even when you control for income and education (except Asian immigrants), they are less likely to do so than natives of the same race/ethnicity. Again, this completely vindicates Wax, since it suggests that not only do immigrants fail to assimilate by adopting the norms of natives, at least white natives, but their descendants do even worse than them. (Because of ethnic attrition, it’s possible that the effect is somewhat inflated, but it’s large enough that, unless you make ridiculous assumptions, this is unlikely to make it go away.) In light of this fact, it’s truly incredible that, even though they analyzed the same dataset, Nowrasteh and Forrester reached the opposite conclusion. I’ve seen countless people citing their analysis on social media to vilify Wax, on the ground that it shows that her claim about littering was racist, when it fact a more careful analysis of the data clearly supports this claim.

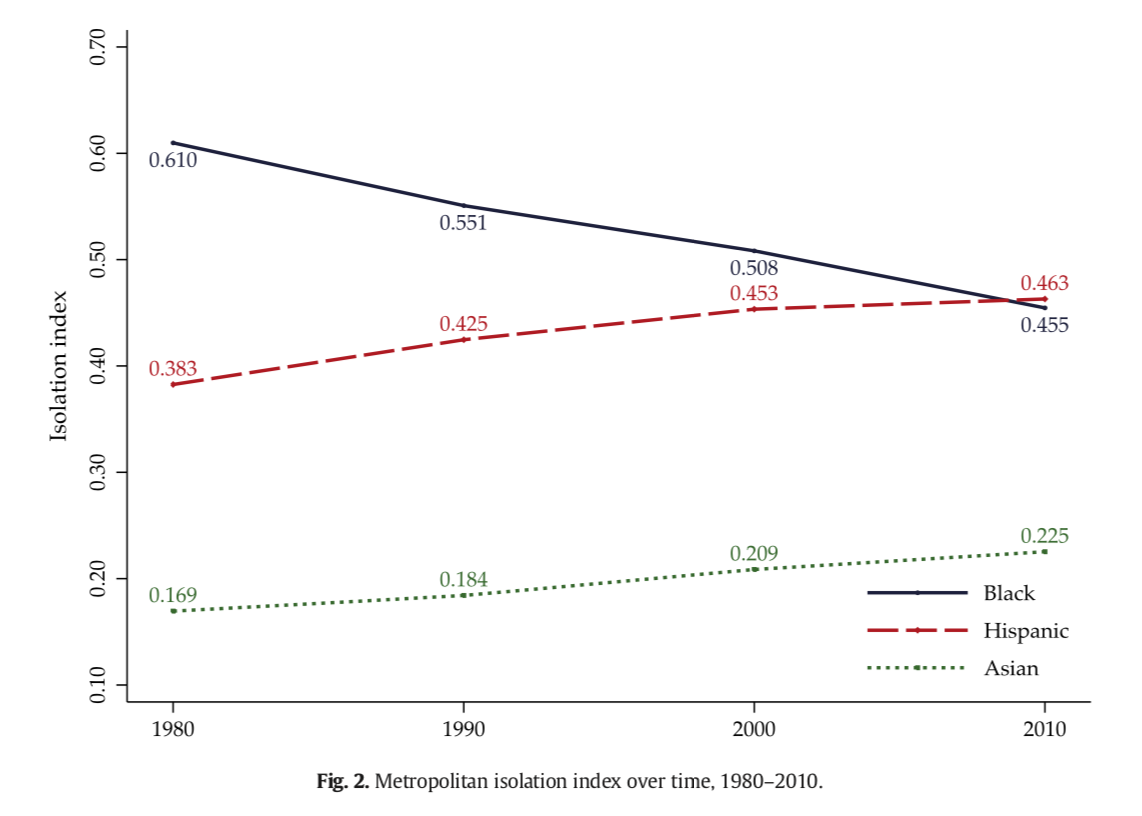

Of course, given the kind of data I have used, even a careful analysis has severe limitations and one should be extremely prudent in interpreting the results. There are many ways in which they could be misleading, but I’m only going to mention a few. First, as I explained above, insofar as members of different racial/ethnic groups are more likely to report trash in their neighborhood because members of different groups are more or less culturally disposed to litter, we should expect the relationship to be moderated by the amount of residential segregation. However, segregation varies a lot by racial/ethnic group, which could bias the comparisons between racial/ethnic groups one is tempted to make based on the results presented above. There are many ways to measure residential segregation, but in this context the isolation index seems particularly appropriate, though not ideal. Here is a graph from this paper which shows the evolution of this index over time for blacks, hispanics and Asians. The isolation index is defined as the average proportion of people of a group in the neighborhood of someone of that group. It measures the extent to which the members of a group live in neighborhoods inhabited by people of the same group.

The isolation index is defined as the average proportion of people of a group in the neighborhood of someone of that group. It measures the extent to which the members of a group live in neighborhoods inhabited by people of the same group.

As you can see, by this measure, Asians are much less segregated than blacks and hispanics. This isn’t surprising given that Asians are a much smaller share of the population in the US than either blacks or hispanics. Depending on who else typically lives in their neighborhood, this might bias the effect we have found upward or downward. For instance, if Asians tend to live around white people and white people tend to litter less, my analysis will make them look better than they really are because the adverse effect they might have on the amount of trash in the streets near where they live would be diluted by the beneficial effect their white neighbors have. On the other hand, if Asians tend to live around other blacks and hispanics, my analysis will make them look worse than they are, because some of the trash they report seeing in their neighborhood will have been thrown in the streets by their black and hispanic neighbors. As far as I know, in the US, Asians are more likely than whites to live around non-whites, but they are more likely than blacks and hispanics to live around whites. It’s impossible to know precisely how this affects the estimate of the coefficient for Asians.

The same concern applies to how including the income and education of respondents as covariates in the model is supposed to adjust for institutional discrimination against poor and low-information people with respect to waste disposal. Indeed, it’s possible and even likely that poor and uneducated people in different racial/ethnic groups are not segregated on socio-economic criteria to the same extent, in which case the inclusion of income and education as covariates will not remove the effect of this kind of discrimination to the same extent for all racial/ethnic groups. For instance, if poor white people are more likely than poor non-whites to live around middle-class people (which they are), they might be less likely to report the presence of trash in their neighborhoods than poor non-whites even if they didn’t litter less, just because they would benefit from living around middle-class people who don’t litter and clean the streets. I tried to interact the income and education covariates with the race/ethnicity dummies, but except perhaps for Asians it didn’t meaningfully affect the coefficients of the race dummies and none of the coefficients of the interaction terms were statistically significant. However, this could just be the result of a lack of power, so I wouldn’t reject this hypothesis just yet.

Moreover, it could be that, in addition to institutional discrimination against poor and uneducated people, there is discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities which results in subpar waste disposal services in their neighborhoods. This would induce a relationship between race/ethnicity and the propensity to report the presence of trash in one’s neighborhood even if non-white people didn’t litter more. Based on my admittedly non-representative experience in Ithaca, I’d say this explanation is unlikely, because as far as I can tell over there the cleanliness of a neighborhood depended only on the behavior of the residents (e. g. whether they littered and put out their trash with the right tags on at the right time), but I obviously can’t generalize from my experience and perhaps it’s different in other parts of the US. If institutional racism affects waste disposal, including covariates for income and education will not help with that, even if the amount of socio-economic segregation doesn’t vary by race/ethnicity.

EDIT: Another possible confounder, which I should have mentioned, is population density. As Divalent points out in the comments, the amount of trash in the streets is probably affected by population density, since there is going to be more littering in more densely populated areas. Since immigrants and racial/ethnic minorities are more urban than white natives, the fact that I didn’t control for population density probably confounds the results. Like I said, there are many things which could confound the analysis and I can’t mention all of them, but this issue seems particularly important so I figured that I should add a brief discussion of it. In some of the previous editions of the American Housing Survey, there was a variable indicating whether the respondent was living in a rural, suburban or urban area, which I had actually planned to add as a covariate, but apparently it’s not available in the 2017 edition of the survey so I couldn’t do it. (Perhaps I will try to get the data from the previous editions of the survey to see if including this variable as a covariate makes any difference.) I did try to run the analysis by excluding respondent who don’t live in a metropolitan area and it didn’t change the results, but there is still a lot of variation with respect to population density in metropolitan areas and it’s probably associated with place of birth and race/ethnicity, so this doesn’t eliminate the concern.

I have no doubt that population density confounds the results to some extent, but I also don’t think it can explain everything. Indeed, the results of the analysis I did also show large differences between non-white groups that are presumably equally urban, which would not be the case if the disparities we see in the data were only the result of differences in population density. For instance, according to the analysis, South Asians do much better than non-hispanic white natives, yet presumably they are more urban. Meanwhile, Asian immigrants do much better than native-born Asians, yet I don’t think they live in more densely populated areas and, in fact, I think it’s probably the opposite. But again I don’t deny that it’s a concern and this should be a reminder that, with this kind of data, we can’t say anything for sure. ANOTHER EDIT: On Twitter, Robert VerBruggen suggested that I control for population density by including the variable BLD, which indicates the type of housing unit in which respondents live. The categories are mobile home or trailer, one-family house (detached), one-family house (attached), 2 apartments, 3-4 apartments, 5-9 apartments, 10-19 apartments, 20-49 apartments, 50 or more apartments and boat, RV, van, etc., so it’s probably a good proxy for population density. When I include this variable in the model, blacks and hispanics look a little bit better, but it doesn’t meaningfully affect the results, in line with the argument I just made. But I agree that models which include this variable are superior, so I have updated the code on GitHub.

Of course, other limitations of my analysis could mean that, compared to whites and some groups of non-whites, hispanics are even more prone to littering than what the results suggest. For instance, the data from the American Housing Survey are based on self-report, which could be misleading for between-group comparisons. In particular, it isn’t unreasonable to suppose that immigrants from poor countries, where there is often a lot of trash in the streets, are less sensitive to this nuisance and therefore less likely to report it than natives. This concern doesn’t apply to non-whites born in the US, but since most hispanics are foreign-born, it could easily bias the analysis in their case. The truth is that, with this kind of data, we can’t say anything for sure. However, this doesn’t mean that it’s reasonable to look at the results of the analysis I conducted and conclude that we have no reason to think that most groups of non-whites litter more than non-hispanic whites, because that’s clearly what the data suggest and it would be dishonest to say otherwise.

Another piece of evidence was uncovered by Steve Sailer, who pointed out a while ago that, in a poll conducted in Texas back in 2002, 30% of hispanics but only 19.3% of the general population admitted to have “discarded major items such as cans, bottles and fast food trash”. Since back in 2000, hispanics were 32% of the population in Texas, it follows that hispanics were about twice as likely as non-hispanics (including 11% of blacks) to admit to this practice. According to the same poll, 9% of hispanics admitted to have “discarded minor items such as cigarette butts, candy wrappers and paper”, whereas only 5% of the general population did. Thus, by the same reasoning as before, they were almost four times more likely to admit to this practice. Of course, it could be that hispanic respondents were just more truthful, but this disparity is really huge and, together with the results of my analysis, I’d say that you’d have to be completely unreasonable to bet that hispanics don’t litter more than whites. Again, I’m not saying we have conclusive proof that hispanics and some other non-whites litter more than whites, but it sure as hell looks that way.

It’s possible that, if we had better data, we’d realize that it’s not the case, but for the moment we don’t. In any case, what is certain is that, to the extent that the data show anything, they clearly favor Wax and undermine the optimism of pro-immigration advocates on the assimilation of immigrants and their descendants. Again, while the issue of littering may seem trivial, this behavior is likely correlated to other anti-social behaviors. In general, the evidence is overwhelming that, in both the US and Europe, some groups of immigrants and/or their descendants disproportionately engage in various anti-social behaviors. (Moreover, the groups of immigrants in question are generally the largest, which explains why people notice this and often don’t use a qualifier when they complain about “immigration”.) Of course, it doesn’t follow that we should restrict immigration, since there may be other considerations against it, especially humanitarian reasons. Personally, I don’t deny such reasons exist, but I also don’t think they are sufficient to justify admitting as many immigrants as we do, let alone increasing their number. Having said that, I also think it’s something reasonable people can disagree about, so I respect people who disagree with me on that point. However, what I don’t respect is people who, out of stupidity or dishonesty and very often both, ignore or misrepresent the evidence about the problems caused by immigration. Of course, plenty of people on my side of the debate also ignore or misrepresent the evidence about immigration, but they have almost no support in academia and the media.

On the other hand, as long as it’s done to support immigration, scientists and journalists have no problem misrepresenting the evidence or even flatly lying about it and, not only are they not punished by their colleagues for it, but they are even praised. In that respect, it’s remarkable that Nowrasteh and Forrester, who analyzed the same dataset as me, ended up concluding that it didn’t support Wax’s argument on littering, which is precisely the opposite of the truth. It’s equally remarkable that, although the problems with their analysis were obvious, many pundits, social scientists and journalists uncritically shared it and used it as a cudgel to beat on Wax. I’m sure that, in some cases, they were aware of the problems with the analysis and made a conscious choice to endorse the post anyway, but I suspect that, in even more cases, they didn’t even notice the problems, even though they clearly don’t lack the background technical knowledge to detect them, because their pro-immigration ideology had put their critical faculties to sleep. I’m also sure that many other social scientists noticed the problems and, while they didn’t share and endorse Nowrasteh and Forrester’s post, they also didn’t say anything because they knew it would damage their reputation among their peers, even though they would have been right. This is another good example of why more ideological diversity in social science is important and why you simply can’t trust social scientists on issues such as immigration where they are overwhelmingly on just one side of the debate.

P. S. Just as I was finishing this post, I was informed that Nowrasteh and Forrester had published another post on the same topic, using data about calls requesting city cleanup services in San Francisco. They don’t find any relationship between the share of hispanics in a neighborhood and the number of calls requesting cleanup. They also don’t find any relationship with the share of foreign-born individuals, but since many foreign-born individuals in San Francisco, a city that is predominantly white and Asian, are well-off and highly educated expats working in tech, this is not particularly surprising. In fact, they even find a negative association between the share of non-citizens and the number of calls requesting cleanup, which for the reason I just gave is what you would have expected. I have read it pretty quickly and haven’t given it much thought, but my first impression is that it’s not as bad as their previous post. (However, the title claims that “immigrant neighborhoods are correlated with few trash complaints in San Francisco”, which is inaccurate, since as we have seen they only find a significant relationship with non-citizens, which is not the same thing as immigrants.) The most obvious problem with this analysis is that, if indeed hispanics litter more, then you would also expect them to be less likely to call city services, because it presumably means they don’t care about litter as much as other people. Thus, Wax’s hypothesis doesn’t imply there will be more calls requesting city cleanup services in neighborhoods where the share of hispanics is higher and is even compatible with there being less calls requesting cleanup in those neighborhoods, so this isn’t really a good test of it. To be fair, Nowrasteh and Forrester point out the problem in their post, though I think they minimize it. They say that since anyone can call city services to request cleanup in any part of the city, even if they don’t live there, it should increase confidence in their results. But let’s be realistic, although I’m sure it sometimes happens, on the whole I think it’s pretty clear that people don’t call city services to request cleanup in areas where they don’t live. Finally, even if that were not the case and this was good evidence against Wax’s claim, San Francisco is just one city. Nowrasteh is right that, if the data had shown a positive association, Wax’s side of the debate would have said it’s evidence in favor of her claim, but a double standard is arguably justified in this case since the asymmetry is real. I’m also not sure that including neighborhood fixed effects is a good idea, but I’d have to think more about this. Since I criticized Nowrasteh for not sharing his code above, I should also note that, in this post, he and Forrester their dataset is available upon request. I think one shouldn’t even have to ask, and I hope they will also share their code, but it’s a step in the right direction if they do what they say.

EDIT: Alex Nowrasteh just informed me that, if he ignored me before when I asked for his code, it’s because he had me muted on Twitter until today.

I had you muted on twitter until today. That’s why I never responded. If you want my code, email me. I share code with anyone who asks. pic.twitter.com/WV6Kpq4iMo

— (((The Alex Nowrasteh))) (@AlexNowrasteh) December 19, 2019

I didn’t know that, but it’s true that we had a spat a few months ago on Twitter and it wouldn’t surprise me if he didn’t want to hear from me after that, so I have no reason to doubt the truth of what he says and therefore I retract my criticism of him on this point. I still think one shouldn’t even have to ask for it, but if he shares his code with anyone who asks for it, he’s still doing better than most researchers and it would be unfair to single him out.

How can you control for population density? I mean, if the proportion of litters was independent of any factor (race, ethnicity, origin, etc), people who live in densely populated areas (e.g., 1 dwelling per every 30 ft of street frontage) would see more litter from their front door than those in less dense areas (e.g., one dwelling every 150 ft of street frontage). I think it is safe to assume that poor people are more likely to live in a densely populated neighborhood, and situated in areas where litter would be only one of many visually blighting aspects of street view.

Also, age demographics: kid are less responsible; more kids = more litter (based on my personal lived experience, lol!).

Thanks, I actually thought about population density when I did the analysis, but I couldn’t find any variable to control for that. Still, it’s a real concern, so I added a brief discussion of this point in the post. I’m much less concerned about age, although I agree it’s probably associated with littering, but perhaps I will try to do something about that.

The data really do seem far from ideal for looking into this.

If memory serves, the Project on Human Development in Chicago collected observational data on physical disorder (including, but not limited, to litter), aggregated to the neighbourhood level, which I think is publicly available. Anyone seriously interested in this should probably have a look into this data (I’m not going to do this). Drawback: It’s from the mid-to-late nineties.

Thanks, I don’t know if or when I will have time, but it might be worth checking this dataset out.

” If you go up to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, or Yankee territory, right? Or versus other places that are ‘more diverse,’ you are going to see an enormous difference. I’m sorry to report. ”

I found this quote ironic, because Stockbridge is best known as the site of the epic song about littering, “Alice’s Restaurant.”

Surely another issue with using the AHS data in this particular instance is that perceptions of what constitutes a “small amount of trash” vs. a “large amount of trash” will vary considerably between different groups (but let’s be generous and assume that “no trash” means what it means). Having lived in the developing world myself for a few years, I know that my perception of an ‘acceptable’ level of littering certainly changed (at least while I was there).