Chatham House, a prestigious think tank in London, recently published a study about the public/private divide in Europe on various political issues. Here is a brief description of the study, taken from the introduction of the paper:

This research paper offers insights into these attitudes. It is based on a unique survey conducted between December 2016 and February 2017 examining attitudes to the EU, as well as to the state of domestic and European politics and society, in 10 countries: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK. The survey covered the two following groups:

- A representative sample of the general public in each country, comprising respondents aged 18 or over, using gender, age and geographical quotas, with 10,195 respondents surveyed online.

- A sample of members of the ‘elite’ – i.e. individuals in positions of in uence at local, regional, national and European levels across four key sectors (elected politicians, the media, business and civil society) – with 1,823 respondents (approximately 180 from each country) who were surveyed through a mix of telephone, face-to-face and online interviews.

The approach was to examine opinions across the European body politic, and for this reason this paper does not explore variations between national subsamples. The elite survey predominantly targeted those based in the member states rather than in Brussels or the EU institutions. While the term ‘elite’ is liable to different interpretations, it serves as a useful descriptor to distinguish between the general public and those individuals likely to have greater interest and in uence in shaping the direction of the EU in the years to come.

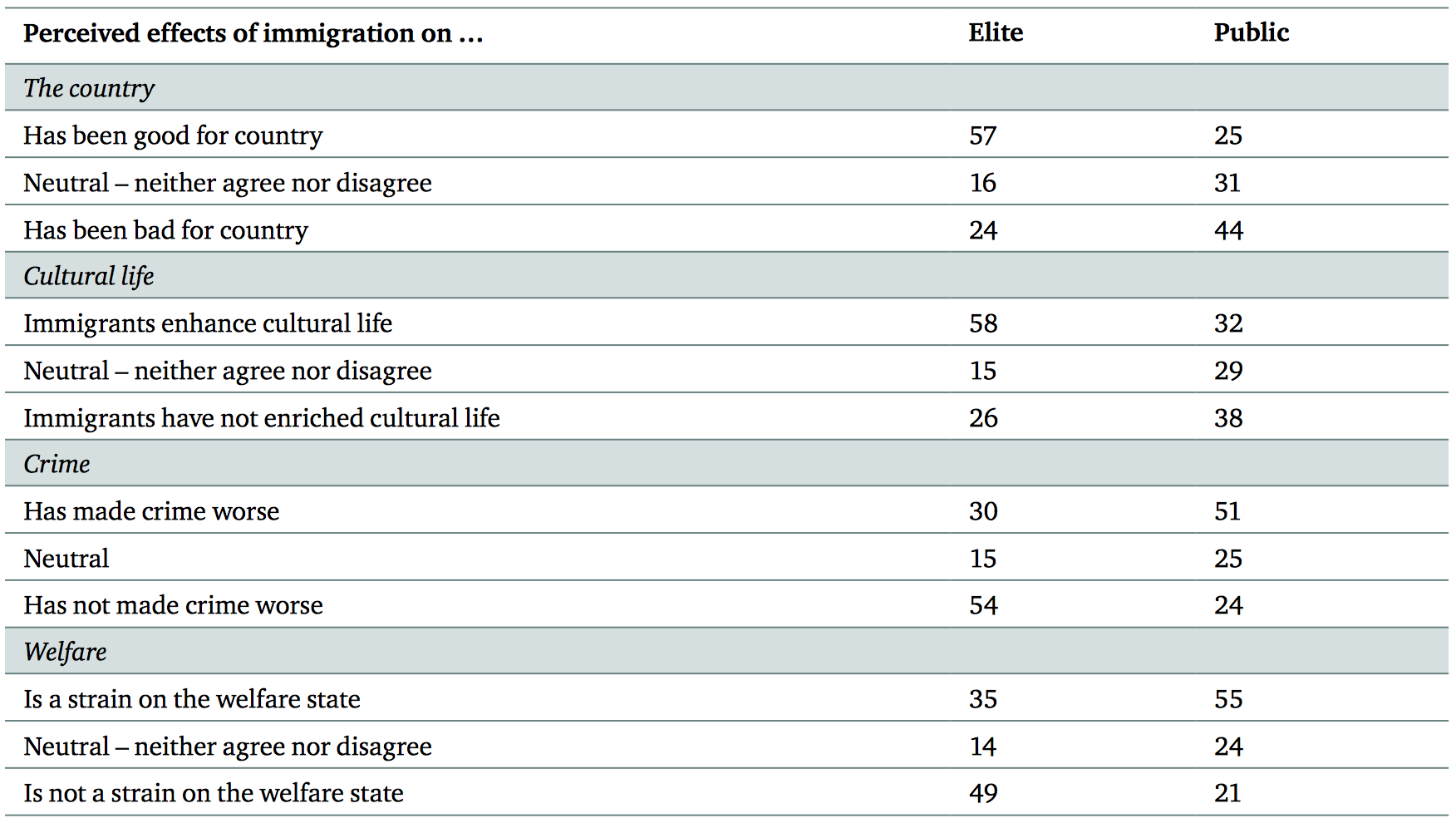

There are lots of interesting things in this study, but perhaps the most striking is what it reveals about the public/elite divide on immigration:

It’s as if people in the elite were mostly protected from the bad consequences of immigration, but not from its benefits, while the opposite were true for most people in the public… (A study showed a similar phenomenon in the US, although there is less opposition to immigration overall here, which is not saying much given how much opposition there is to immigration in Europe.) What is really striking is that, on every single point raised in that poll, people in the public are right and people in the elite are wrong. At least, they are if we’re talking about the immigration of poor, unskilled and non-Western people, but this is what people have in mind when they complain about immigration. In fact, not only is the public right, but it’s obviously right.

Of course, the sophisticates don’t know that, because they haven’t actually read the literature which they claim shows the public is mistaken about immigration. So they ascribe the hostility to immigration among the public, which is off the charts, to bigotry and ignorance. As soon as I have more time, which probably won’t be until a few months from now, I plan to publish a series of very detailed posts in which I discuss the literature on the effects of immigration in the West. In the meantime, if you are convinced that the elite is right and that immigration is great for Europe, you should ask yourself why, if members of the elite are right, they have to lie all the time about this. For instance, you should ask yourself why, if immigration really doesn’t make crime worse, the French government under Jospin gave instructions to the police not to release any names when communicating to the press or why journalists systematically replace non-French names by French names when they write on crime. Similarly, you could ask yourself why both the authorities and the media covered up the sexual assaults perpetrated by migrants in Cologne and many other cities throughout Europe in 2016, before the truth finally came out. If these were isolated incidents, you couldn’t conclude much from them, but the cover-up is systematic. Maybe it’s just me, but when I think what I’m saying is true, I don’t have to lie about it.

In Chile, where there is a lot of immigration from poorer Latin American countries, immigrants compete for scarce public social services with Chileans and that produces resentment and anger.

For example, the other day I had to wait, along with many other older people, some of them with canes or crutches, for an hour and a half to get a medical procedure approved in the state medical insurance institute (Fonasa). There were lots of new Latin American immigrants also waiting, all or almost all of them younger than we senior citizens, who in the past might have gotten our procedures approved and paid for in, say, 10 or 15 minutes.

The Chilean political and economic elite do not wait on line in the state medical insurance institute because, unlike the poor and the middle class (that’s me), they have private medical insurance policies, which, for someone my age (71) and income, are out of reach. Immigrants do not affect the access of the elite to public social services because the elite do not use public social services.

The obvious solution would be for the government to hire a few more people to deal with the lines in the state medical insurance institute and to re-engineer the procedures, which are outdated and unnecessarily bureaucratic.

In general, the recent Latin American immigrants to Chile seem hard-working, polite and friendly and I welcome their presence. I do hope and pray that the government will pay a bit of attention to the problems in public social services that their presence gives rise to and take measures to solve those problems.

May I know how you ended up in Chile and when? I’m curious to know more. I should say that I know absolutely nothing about immigration in South America, except for the immigration that took place a long time ago.

I’ve been in Chile since 1979. I met a Chilean woman in Brasil, she got pregnant and I came to Chile with her.

How did I get to Brasil? I left the U.S. in 1977 searching for “something” or “someone” (I don’t recall what or whom) and ended up in Sao Paulo, teaching English “off the books”.

In recent years Chile has been a model of economic growth in Latin America. It has been politically stable since the return to democracy in 1990 after the Pinochet dictatorship. Public social services, such as education and public healthcare, which appear needlessly bureaucratic and insufficient to Chileans and long-term residents, are attractive to people who come from Latin American countries where such public social services are absent or much more backward. So we get a sizeable immigration from other Latin American countries, neighboring ones like Peru and Bolivia and farther off ones like Venezuela (which is a disaster) and Haiti (another disaster).

When I arrived here, there was almost no immigration and little tourism, due to the Pinochet dictatorship. Although procedures to become a resident were incredibly complicated and bureaucratic then (as now), almost no one else wanted to become one back then and so

there were no lines, no waiting, the police from the division in charge of immigration joked with me about what I was up to when I went to their offices.

I’d expect liberal authorities in France or the UK to cover up some immigrant crime whether or not immigrants “make crime worse”. They experience very strong pressures to not seem racist, xenophobic ect, so I don’t see cover ups as giving us much information.

They wouldn’t be afraid of being seen as racist if immigrants and the descendants of recent immigrants didn’t commit such a disproportionate share of crime, because in that case they’d rarely even mention crimes committed by immigrants or descendants of recent immigrants. For instance, journalists wouldn’t be afraid of being accused of racism because they give the names of suspects, since those names would only sound foreign very rarely.

I’m not convinced.

The pressures to not be seen as xenophobic or racist in the places you mention are quite strong and not really sensitive to things like proportions, shares, or stats.

Same with the pressure to not be seen as sexist, as you have written about before.

What do you/the survey mean by “make crime worse”? If you mean more crimes are committed, well then adding additional people from any population will of course make crime worse. Are we saying immigrants are more likely to commit crimes? If so, more likely then whom–the average naturally born citizen, or a naturally born citizen of the same economic status/age/sex etc? Perhaps this is just elites and the general public interpreting questions differently and doesn’t actually mean anything.

Furthermore, its not clear to me that all crimes are the same. Even if immigrants are more likely to commit crimes (a big if) perhaps showing compassion by allowing refugees from war torn countries, at the expense of some additional petty crimes, will prevent a future 9/11 by making it harder for terrorist cells to recruit.

As I said in my post, I plan to discuss that and other question in details as soon as possible, but right now I really don’t have time. (When I say that I will discuss that in details, I’m not joking. I will go over these issues in excruciating details. In fact, a long-term project of mine is to turn that series of posts into a book when it’s done, so I really plan to do this very seriously.)

I will just say that the notion that one might prevent another 9/11 by allowing in more people who belong to the group most likely to commit that sort of things strikes me as rather extravagant. If people really want to prevent another 9/11, they should protest against Western interventionism in the Middle East, which is by far the major factor over which we have any control.

In the vast majority of cases, however, the people who are pushing for pro-immigration policies are the same who are constantly pushing for more interventions abroad in the name of human rights. Libertarians and socialists are pretty much the only exceptions, but there are very few of them.

I am looking forward to this series of posts or/and your book on this subject. It’s definitely something I’d be curious to know more about, beyond what one can learn from the partisan chatter in MSM and on social media. And judging from your posts on Syria and Trump/Russia, I trust your take to be both fair and exhaustive.

Is your thesis what is currently keeping you so busy? Not sure if you’re willing to share such details with readers of your blog, but what is your expected timeline on that and what are you looking to do afterwards? Do you think you’d like to stay in the US or return to France?

Sorry for the late reply. I am really swamped and I tend to forget comments. The reason why I’m so busy is a combination of wrapping up my PhD and getting ready to move, as I’m actually going back to France in 2 weeks. I’m not sure what I’m going to do yet, which is another thing that keeps me busy. But I’ll most likely stay in France or at least in Europe.

In France you could advise Macron (or any other political leader) on the “American” mentality. Your grasp of the U.S. political scene (and of the American version of the English language) is very impressive. I would wager that there are few people in France who understand how American politics works as well as you do.

In fact, back in France you’re probably going to spend a lot of time irritated by how little French people understand about the U.S. , how they see it in cliché terms, how they generalize about it, and finally, how little interest they have in learning anything more about it than the clichés.

Can you recommend anything good to read on how to draw the elite/public distinction? Do you have a view? Some take rich liberals to be synonymous with the elite, but that can’t be right. You are a member of the elite because you are attending Cornell, but you are not clearly a liberal (or at least a progressive). I don’t mean anything pejorative by that. PhD students at Ivy League institutions are clearly members of the elite. But you don’t share the view of people you call elites, so perhaps you are a wayward elite? Or perhaps you have some alternative view of what it is to be elite? The words ‘elite’ and ‘sophisticate’ can’t just be restricted for whoever has a view opposite to your own. So, it would help in these posts to get clearer on who you take to be one and whether you think you are expressing the view of one—if the Chatham pollsters had quizzed you, they would have recorded your response as an elite one.

I don’t think I often use the term “elite” myself. I use it in this post in the sense in which Chatham used it in that study. I quoted the passage where they describe who they considered members of the elite for the purpose of this survey. I don’t think I qualify, even though I’m a PhD candidate at Cornell. I’m certainly part of what I call the sophisticates, i. e. educated people who have jobs that require relatively high cognitive abilities, though my views tend not to line up with the majority among that group. If you read the Chatham study, they actually distinguish a subgroup among the public, which corresponds to what I call the sophisticates and whose views line up more with those of the elite. Both the concept of elite and that of sophisticates are vague, but that’s not a problem, since many vague concepts are very useful. I’m also not suggesting that everyone who belongs to either group agrees on everything. This is not true of any group. But on many key issues, they do agree to a very large degree.